Harmonic Oscillators (Part 2)

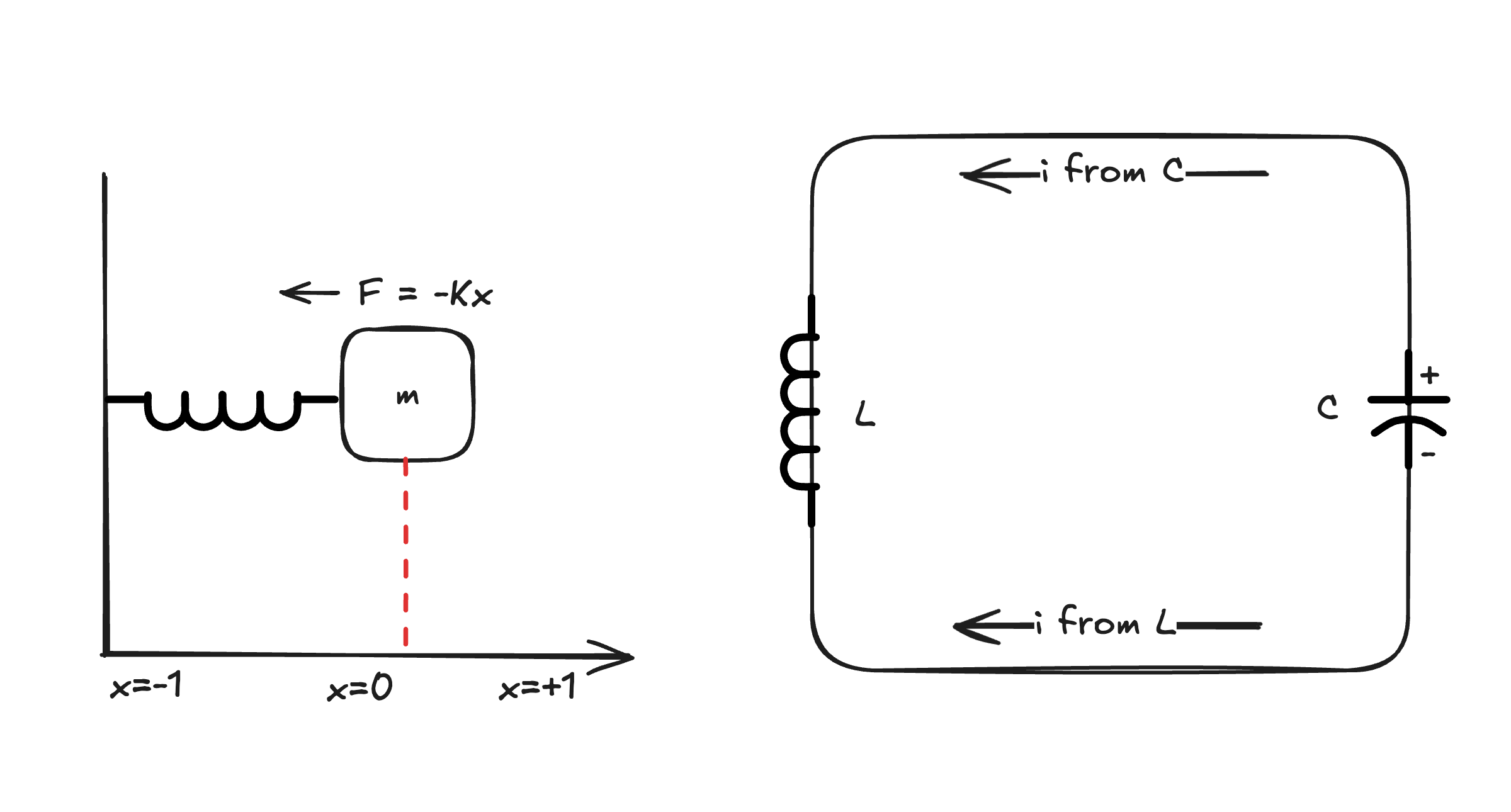

This is a second post on electrical circuits and their similarity to mechanical oscillators. The previous post covers the mechanical harmonic oscillator and the LC circuit. This post focuses on the RLC circuit and its applications.

RLC Circuits

The LC circuit is idealized without any resistance ($R$). In practice, circuits do have resistance and will not conserve energy (losing some energy to heat). We can add $R$ back in to form an RLC circuit. We can further add an A/C voltage source which acts like a driven harmonic oscillator and is used in a variety of frequency filters. Before deriving the Lagrangian and equations of motion for the RLC circuit, we can first visualize it with this great circuit simulator by Paul Falstad.

You can refer to Section 8.2.4 in Purcell & Morin’s textbook for more background. The simulation above was modeled after Figure 8.11 in particular ($L$ = 100 mH, $C$ = 10 nF, $R$ = 20-200 Ohm, $\mathcal E_0$ = 100 V, $\omega$ = 158.2kHz). Try sliding the resistance to see how it affects the circuit’s max current (the max current should range between 500mA and 5A as advertised by the textbook).

Concretely, the two additions to the LC circuit that make an RLC circuit are:

- Resistor $R$ that has voltage $v_R = iR$

- External A/C electromotive force $\mathcal{E} = \mathcal{E}_0 \cos{(\omega t)}$

Lagrangian

Recalling the Lagrangian for the LC circuit:

\[\begin{align*} \mathcal L &= \frac{1}{2C} Q^2 - \frac{1}{2}L (\frac{dQ}{dt})^2 \end{align*}\]We can actually use this as-is for the RLC circuit. What will change however, is the Euler Lagrange equation. Before we had:

\[\begin{align*} \frac{\partial \mathcal L}{\partial Q} - \frac{d}{dt} \frac{\partial \mathcal L}{\partial (\frac{dQ}{dt})} = 0 \end{align*}\]We now need to add two new terms that generalizes the Lagrangian to include non-conservative forces:

Generalized force for A/C voltage:

\[Q_{ext} = \mathcal{E}_0 \cos{(\omega t)}\]Generalized force for resistance:

\[Q_{res} = -\frac{\partial F}{\partial (\frac{dQ}{dt})}\]

$Q_{res}$ is also known as a Rayleigh dissipation function and takes the place of friction from our mechanical oscillator (also known as damping). The Euler Lagrange equation now looks like:

\[\begin{align*} \frac{\partial \mathcal L}{\partial Q} - \frac{d}{dt} \frac{\partial \mathcal L}{\partial (\frac{dQ}{dt})} = Q_{ext} + Q_{res} \end{align*}\]The only thing left undecided is the form of $F$ for $Q_{res}$. I actually needed to cheat and work backwards from the desired result which is given by Kirchhoff’s voltage law:

\[\begin{align*} v_L + v_R + v_C &= \mathcal{E} \\ \text{or,}\quad L\frac{d^2Q}{dt^2} + R(\frac{dQ}{dt}) + \frac{Q}{C} &= \mathcal{E}_0 \cos{(\omega t)} \end{align*}\]A function for $F$ that works is:

\[F = \frac{1}{2}R (\frac{dQ}{dt})^2\]which is quadratic in $\frac{dQ}{dt}$ and is related to the power ($P = vi = i^2R$) by $P = 2F$. Going back to the mechanical oscillator, the dissipation function caused by friction would be $F_{mechanical} = \frac{1}{2}bv^2$ where $b$ is the damping coefficient analogous to resistance $R$. This gives $Q_{mechanical} = -bv$ and a mechanical “power” as $P_{mechanical} = Fv = v^2 b$. So, we see a pretty good match between the RLC circuit and the damped harmonic oscillator.

Regardless, $F$ gives the correct Kirchhoff loop equation and now we are ready to solve for the equations of motion.

Equations of Motion

Our goal is to solve this second order differential equation we got from the Lagrangian above.

\[\begin{align*} L\frac{d^2Q}{dt^2} + R(\frac{dQ}{dt}) + \frac{Q}{C} &= \mathcal{E}_0 \cos{(\omega t)} \end{align*}\]This will actually be easier to convert the charge ($Q$) back to current ($I(t)$):

\[\begin{align} L\frac{dI(t)}{dt} + RI(t) + \frac{1}{C}\int I(t) dt &= \mathcal{E}_0 \cos{(\omega t)} \label{eqn:kirchoff} \end{align}\]It is possible to find a solution to this differential equation with just trigonometric functions (see Section 8.2 of Purcell & Morin). Instead, we will solve this with complex exponential functions (see Section 8.3 of Purcell & Morin).

I will now be using $I(t)$ for current instead of $i$ since we will soon see imaginary $i$, complex number $\tilde I$, and complex current $\tilde I(t)$.

Mathematical Interlude

In the next section, we will be using complex numbers to solve differential equations. Here is a list of identities we will make use of:

- Definition of an imaginary number: \(\begin{align} i^2 = -1 \label{eqn:i} \end{align}\)

Definition of a complex number:

\(\begin{align} z = a + ib \label{eqn:complex_number} \end{align}\) where $\Re{[z]} = a$ and $\Im{[z]} = b$. The complex conjugate to $z$ is $\bar z = a - ib$.

- \[\begin{align} \exp{i\theta} = \cos{\theta} + i\sin{(\theta)} \label{eqn:eulers_formula} \end{align}\]

- Moving an $i$ from the denominator: \(\begin{align} \frac{1}{ib} = \frac{1}{ib}\frac{i}{i} = -\frac{i}{b} \label{eqn:i_frac} \end{align}\)

- Multiplying by a complex conjugate: \(\begin{align} (a + bi)(a - bi) &= a^2 + b^2 \label{eqn:conjugate_product} \end{align}\)

- Polar form: \(\begin{align} (a + bi) &= r\cos{(\theta)} + ir\sin{(\theta)} \nonumber\\ &= r(\cos{(\theta)} + i\sin{(\theta)}) \nonumber\\ &= r \exp{i\theta} \label{eqn:polar} \end{align}\) Where $r = \sqrt{a^2 + b^2}$ and $\tan{(\theta)} = \frac{b}{a}$ using the typical trigonometric identities.

Back to the physics!

An informed guess

For now, trust that using complex exponential functions make things easier to solve $\eqref{eqn:kirchoff}$. But clearly $\eqref{eqn:kirchoff}$ does not yet involve anything of the sort. Can we find an equation involving complex exponentials that is equivalent with $\eqref{eqn:kirchoff}$? The simplest thing to try is to replace any variable with a dependency on $t$ with it’s complex counterpart:

\[\begin{align} L\frac{d\tilde I(t)}{dt} + R\tilde I(t) + \frac{1}{C}\int \tilde I(t) dt &= \mathcal{E}_0 \exp{i\omega t} \label{eqn:complex_kirchoff} \end{align}\]Both $\eqref{eqn:kirchoff}$ & $\eqref{eqn:complex_kirchoff}$ are linear differential equations involving $L$, $C$, $R$ and the emf. To see the exact relationship between the two, consider taking $\Re{[\cdot]}$ of both sides of $\eqref{eqn:complex_kirchoff}$:

\[\begin{align*} \Re{\big[L\frac{d\tilde I(t)}{dt} + R\tilde I(t) + \frac{1}{C}\int \tilde I(t) dt\big]} &= \Re{[\mathcal{E}_0 \exp{i\omega t}]} \\ \implies L\frac{d\Re{[\tilde I(t)]}}{dt} + R\cdot\Re{[\tilde I(t)]} + \frac{1}{C}\int \Re{[\tilde I(t)]} dt &= \mathcal{E}_0 \cos{(\omega t)} \end{align*}\]Where we have used the “linear-enough” property of the $\Re{[\cdot]}$ operator for the LHS and $\eqref{eqn:eulers_formula}$ for the RHS. It seems $\eqref{eqn:complex_kirchoff}$ is the “complex version” of $\eqref{eqn:kirchoff}$. The upshot is that $\tilde I(t)$ will solve $\eqref{eqn:complex_kirchoff}$ and $\Re{[\tilde I(t)]}$ will solve $\eqref{eqn:kirchoff}$ simultaneously! If we set:

\[\Re{[\tilde I(t)]} = I(t)\]Then we will have an expression for $I(t)$ that solves $\eqref{eqn:kirchoff}$.

Before proceeding with solving for $\Re{[\tilde I(t)]}$, we can take a step back and appreciate this strategy. We want to solve $\eqref{eqn:kirchoff}$ for some $I(t)$ but want to avoid the tedious algebra/ trigonometry. Instead, we find some seemingly unrelated yet equivalent statement $\eqref{eqn:complex_kirchoff}$ in the complex domain with an analogous solution $\tilde I(t)$. By solving $\tilde I(t)$, we necessarily solve $\eqref{eqn:kirchoff}$ for $I(t)$. It remains to be seen whether $\Re{[\tilde I(t)]}$ is actually easier to solve than $I(t)$, but we will pursue this in the next section (spoiler alert: using our mathematical interlude, it is).

Solving for $\Re{[\tilde I(t)]}$

Now we will actually solve $\eqref{eqn:complex_kirchoff}$ for $\tilde I(t)$. Since the whole point of this exercise was to cut down on the algebra, we can choose a function that makes this easier:

\[\tilde I(t) = \tilde I \exp{i\omega t}\]Which has one free parameter, $\tilde I$, some complex number we need to solve for. Why is this easier? Because the derivatives and integrals of exponential functions are exponential functions:

\[\begin{align*} L\frac{d\tilde I(t)}{dt} + R\tilde I(t) + \frac{1}{C}\int \tilde I(t) dt &= \mathcal{E}_0 \exp{i\omega t} \\ L \frac{d}{dt}(\tilde I \exp{i\omega t}) + R(\tilde I \exp{i\omega t}) + \frac{1}{C} \int \tilde I \exp{(i\omega t)} dt &= \mathcal{E}_0 \exp{i\omega t} \\ Li\omega \tilde I \exp{i\omega t} + R\tilde I \exp{i\omega t} + \frac{1}{i\omega C} \tilde I \exp{i\omega t} &= \mathcal{E}_0 \exp{i\omega t} \end{align*}\]Which allows us to divide $\exp{i\omega t}$ through the equation:

\[\begin{align*} Li\omega \tilde I + R\tilde I + \frac{1}{i\omega C} \tilde I &= \mathcal{E}_0 \\ \therefore \tilde I &= \frac{\mathcal{E}_0}{Li\omega + R + \frac{1}{i\omega C}} \end{align*}\]Leaving us with $\tilde I$. To simplify $\tilde I$ we will first use $\eqref{eqn:i_frac}$ to move the $i$ to the numerator (of the denominator):

\[\begin{align*} \tilde I &= \frac{\mathcal{E}_0}{Li\omega + R - \frac{i}{\omega C}} = \frac{\mathcal{E}_0}{R + i (L\omega - \frac{1}{\omega C})} \end{align*}\]And then multiply by $\frac{R - i (L\omega - \frac{1}{\omega C})}{R - i (L\omega - \frac{1}{\omega C})} = 1$ and use $\eqref{eqn:conjugate_product}$ to move $i$ to the numerator:

\[\begin{align*} \tilde I &= \frac{\mathcal{E}_0}{(R + i (L\omega - \frac{1}{\omega C}))} \cdot \frac{(R - i (L\omega - \frac{1}{\omega C}))}{(R - i (L\omega - \frac{1}{\omega C}))} \\ &= \frac{\mathcal{E}_0 [R - i (L\omega - \frac{1}{\omega C})]}{R^2 + (L\omega - \frac{1}{\omega C})^2} \end{align*}\]We can write the numerator in polar form $\eqref{eqn:polar}$:

\[\begin{align*} \tilde I &= \frac{\mathcal{E}_0 [R - i (L\omega - \frac{1}{\omega C})]}{R^2 + (L\omega - \frac{1}{\omega C})^2} \\ &= \frac{\mathcal{E}_0 }{R^2 + (L\omega - \frac{1}{\omega C})^2} \sqrt{R^2 + (L\omega - \frac{1}{\omega C})^2} \exp{i\phi} \\ &= \frac{\mathcal{E}_0 }{\sqrt{R^2 + (L\omega - \frac{1}{\omega C})^2}} \exp{i\phi} \\ &= I_0 \exp{i\phi} \end{align*}\]With,

\[\begin{align} \boxed{I_0 = \frac{\mathcal{E}_0 }{\sqrt{R^2 + (L\omega - \frac{1}{\omega C})^2}}} \label{eqn:current_amplitude} \end{align}\]and,

\[\begin{align} \boxed{\phi = \tan^{-1}(\frac{\frac{1}{\omega C} - L\omega}{R}) = \tan^{-1}(\frac{1}{R\omega C} - \frac{L\omega}{R})} \label{eqn:current_phase} \end{align}\]Finally, we can solve for $\Re{[\tilde I(t)]}$:

\[\begin{align*} \Re{[\tilde I(t)]} &= \Re{[\tilde I \exp{i\omega t}]} \\ &= \Re{[I_0 \exp{i\phi}\exp{i\omega t}]} \\ &= \Re{[I_0 \exp{i(\phi + \omega t)}]} \\ &= I_0 \Re{[\exp{i(\phi + \omega t)}]} \\ &= I_0 \cos{(\omega t + \phi)} \end{align*}\]Or,

\[\begin{align} \boxed{\Re{[\tilde I(t)]} = I(t) = \frac{\mathcal{E}_0 }{\sqrt{R^2 + (L\omega - \frac{1}{\omega C})^2}} \cos{(\omega t + \phi)}} \label{eqn:lrc_current} \end{align}\]Which agrees with the result from Section 8.2 of Purcell & Morin. If we are willing to accept the mathematical interlude as given facts, I think this solution is pretty straightforward (if you disagree, check out the trig solution to convince yourself!).

Analysis of $I(t)$

Looking at the amplitude of the wave,

\[\begin{align*} I_0 &= \frac{\mathcal{E}_0 }{\sqrt{R^2 + (L\omega - \frac{1}{\omega C})^2}} \\ &= \frac{\mathcal{E}_0 }{\sqrt{R^2 + (\frac{L\omega^2C - 1}{\omega C})^2}} \end{align*}\]We can see two extremes we want to analyze:

- $R = 0$

- $L\omega^2C - 1 = 0$

For the first case, if $R = 0$, then:

\[\begin{align*} I_0 &= \frac{\mathcal{E}_0 }{\sqrt{R^2 + (L\omega - \frac{1}{\omega C})^2}} \\ &= \frac{\mathcal{E}_0 }{\sqrt{(\frac{L\omega^2C - 1}{\omega C})^2}} \\ &= \frac{\mathcal{E}_0 }{\frac{L\omega^2C - 1}{\omega C}} \\ &= \frac{\mathcal{E}_0 \omega C }{L\omega^2C - 1} \\ &= \omega A \\ \end{align*}\]Where $A = \frac{\mathcal{E}_0 C }{L\omega^2C - 1}$. Ignoring $\phi$ in $\eqref{eqn:current_phase}$ for the moment, this makes $I(t)$ in $\eqref{eqn:lrc_current}$:

\[\begin{align*} I(t) &=\omega A \cos{(\omega t + \phi)} \end{align*}\]Which has the same form of the current we found for the LC circuit previous post.

There is one very big difference however: the $\omega$...

The $\omega$ from the LC circuit (lets call it $\omega_0$ to keep things clear) was actually $\omega_0 = \sqrt{\frac{1}{LC}}$ in our wave equation. This new $\omega$ is the angular frequency of the driven emf source $\mathcal E$ (something we are free to control as an input to the system). What would happen if we set the A/C emf so that $\omega = \omega_0$? Then,

\[\omega = \sqrt{\frac{1}{LC}} \iff L\omega^2C - 1 = 0\]Which was our second extreme case! Further, if $\omega = \omega_0$, then $A$ becomes undefined when $R = 0$. Luckily, $R = 0$ is an idealized case (although negligibly small $R$ is possible). For some fixed $R > 0$, when $\omega = \omega_0$ we see that $I_0$ is maximal (making $I(t)$ the most “active”). $\omega_0$ is the resonant frequency of the circuit and, under these conditions, the $I(t)$ in $\eqref{eqn:lrc_current}$ reduces to that of a single resistor with an EMF:

\[I_{\omega_0}(t) = \frac{\mathcal E_0 \cos{(\omega t + \phi)}}{R} = \frac{\mathcal E}{R}\]In the earlier post we saw that the capacitor’s voltage and inductor’s voltage were equal and opposite in an LC circuit. So this result makes sense as the components cancel each other. Somewhat amazingly, the resonant frequency of the LC circuit is encoded inside the more general LRC circuit with A/C voltage.

RLC Circuit as a Bandpass Filter

It should be clear by now that as $\omega$ goes away from $\omega_0$ the current in the circuit decreases. This can be quantified precisely (i.e. the “peakness” and “width” of this $\max_{\omega}I(t; \omega)$ curve), see discussion in 8.2.6 of Purcell & Morin. Instead, we can revisit the simulation before but let the frequency vary instead of the resistance and see how it affects the circuit’s max current:

You should notice that the current reacts to certain (resonant) frequencies. In this case, $\omega_0$ = 158.2kHz which should yield 5A of current. This is how a bandpass filter works. In radio communications, we can change the resonance of the circuit (with a variable capacitor) allowing us to “tune” into specific frequencies and ignore everything else!