Lorentz Transformation for Electromagnetic Field Tensor

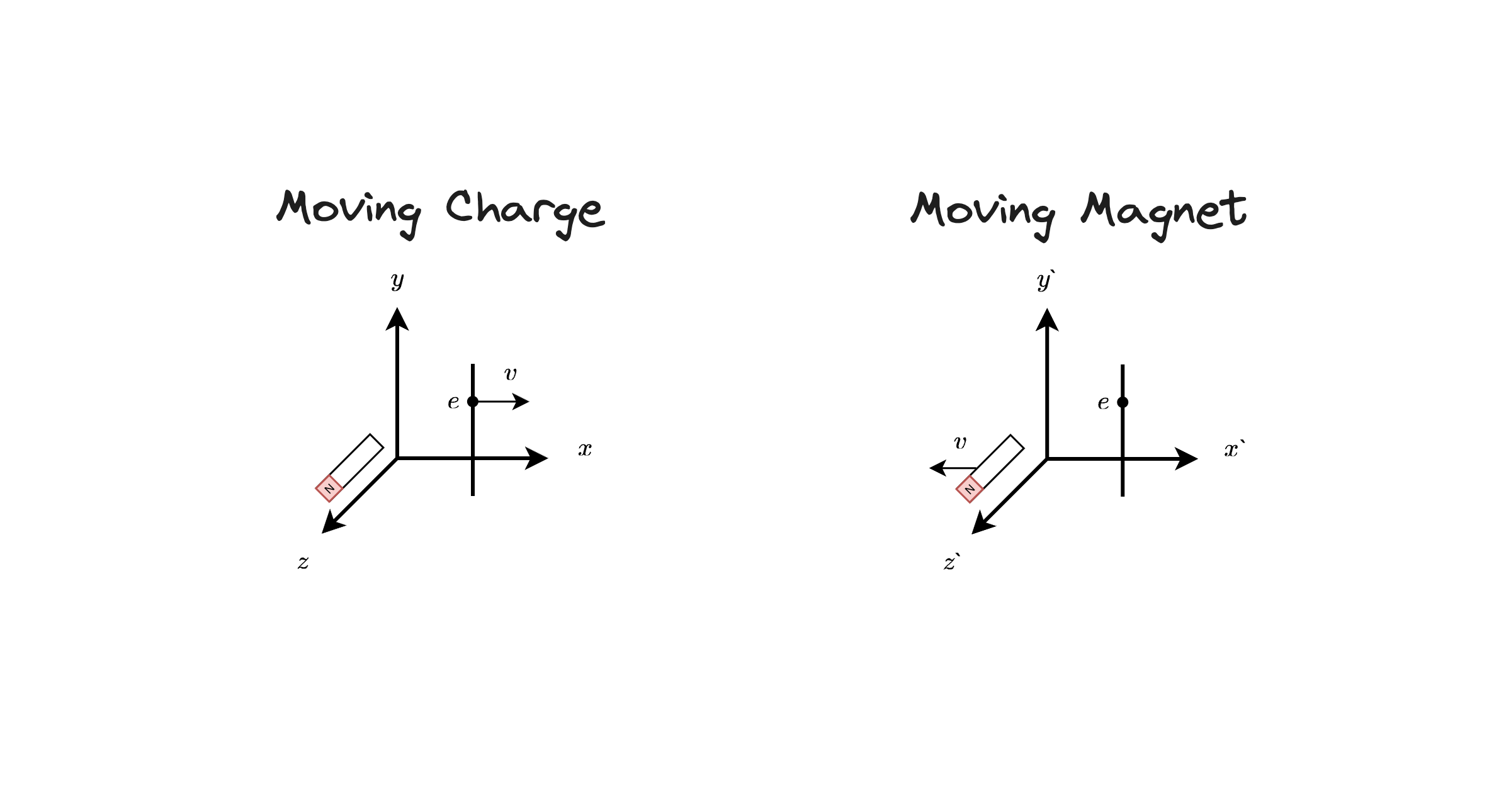

Details of an experiment originally explained in Albert Einstein’s 1905 paper on Special Relativity entitled On The Electrodynamics Of Moving Bodies. The experiment consists of an electric charge and a magnet viewed from two perspectives:

- Moving Charge (stationary magnet)

- Moving Magnet (stationary charge)

The setup is clearly described in the introduction of the paper:

Take, for example, the reciprocal electrodynamic action of a magnet and a conductor. The observable phenomenon here depends only on the relative motion of the conductor and the magnet, whereas the customary view draws a sharp distinction between the two cases in which either the one or the other of these bodies is in motion. For if the magnet is in motion and the conductor at rest, there arises in the neighbourhood of the magnet an electric field with a certain definite energy, producing a current at the places where parts of the conductor are situated. But if the magnet is stationary and the conductor in motion, no electric field arises in the neighbourhood of the magnet. In the conductor however, we find an electromotive force, to which in itself there is no corresponding energy, but which gives rise—assuming equality of relative motion in the two cases discussed—to electric currents of the same path and intensity as those produced by the electric forces in the former case.

Moving Charge Viewpoint

The first perspective of the setup consists of:

- A stationary magnet oriented in the $+z$ axis (positive pole pointing in the $+z$ direction).

- An electric charge moving away from it with velocity $\vec v$ in the $+x$ axis.

Since $\vec v$ is perpendicular to $B_z$, there will be a Lorentz force oriented in the $+y$ direction:

\[\vec F = e(\vec v \times \vec B)\]If we had a wire pointing in the $+y$ direction, this would cause an electric current in the $-y$ direction as successive charges are pushed downwards (recall that the charge, and thus the current, of an electron is considered negative by convention).

Moving Magnet Viewpoint

Now we change our perspective to the electric charge, so that the magnet is now moving:

- A stationary electric charge oriented in the $+x$ axis.

- A magnet pointing in the $+z$ axis moving away from it with velocity $\vec v$ in the $-x$ direction.

Since $\vec v = \vec 0$ for the electric charge, we know that in this perspective, the Lorentz force is zero. Therefore, any force the charge still feels is that of an electric field. This is known as an electromotive force (EMF), which is an electric field created by a moving magnetic field.

Electromagnetic Field Tensor

From the above, we see that magnetic fields must transform into electric fields when we transform to a moving reference frame. But this change in reference frame (from a stationary to moving reference frame) is explained by the Lorentz Transform. So it is natural to ask, is there some description of the experiment that will convert a magnetic field to a electric field under a Lorentz transformation?

The answer is yes, that description is the (covariant) electromagnetic field tensor:

\[\begin{equation} F^{\mu \nu} = \begin{bmatrix} 0 & E_x & E_y & E_z \\ -E_x & 0 & B_z & -B_y \\ -E_y & -B_z & 0 & B_x \\ -E_z & B_y & -B_x & 0 \\ \end{bmatrix} \end{equation}\]Unlike in the previous post, the Lorentz transformation no longer acts on a rank-1 tensor (aka vector) $X^\mu = [t, x, y, z]$:

\[(X')^\mu = {L^\mu}_\nu X^\nu\]but an anti-symmetric rank-2 tensor (aka matrix) containing the components of the electric & magnetic fields:

\[(F')^{\mu \nu} = {L^\mu}_\sigma {L^\nu}_\tau F^{\sigma \tau}\]Where ${L^\mu}_\sigma$ is given by:

\[\begin{equation} {L^\mu}_\sigma = \begin{bmatrix} \frac{1}{\sqrt{1 - v^2}} & \frac{-v}{\sqrt{1 - v^2}} & 0 & 0 \\ \frac{-v}{\sqrt{1 - v^2}} & \frac{1}{\sqrt{1 - v^2}} & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 \\ \end{bmatrix} \end{equation}\]Lorentz Transformation

Now, we have to show that under the Lorentz transformation ${L^\mu}_\sigma$, the electromagnetic field tensor $F^{\sigma \tau}$ starts with a pure magnetic field but is converted to an electric field in $(F’)^{\mu \nu}$.

First, each of the transformed electric field components:

\[\begin{aligned} (E’)_x &= (F’)^{01} \\ &= L^0_{\;\mu} L^1_{\;\nu} F^{\mu\nu} \\ &= L^0_{\;1} L^1_{\;0} F^{10} + L^0_{\;0} L^1_{\;1} F^{01} \\ &= \gamma(-v)\gamma(-v)(-v)(-E_x) + \gamma^2E_x \\ &= \gamma^2E_x(1 - v^2) \\ &= E_x \\ \\ (E’)_y &= (F’)^{02} \\ &=L^0_{\;\mu}L^2_{\;\nu} F^{\mu\nu} \\ &=L^0_{\;0}L^2_{\;2}F^{02} + L^0_{\;1} L^2_{\;2} F^{12} \\ &=\gamma E_y + \gamma(-v)B_z \\ &=\gamma(E_y - v B_z) \\ &=\gamma(E + v \times B)_y \\ \\ (E’)_z &= (F’)^{03} \\ &= L^0_{\;\mu}L^3_{\;\nu} F^{\mu\nu} \\ &=L^0_{\;0}L^3_{\;3}F^{03} + L^0_{\;1} L^3_{\;3} F^{13} \\ &=\gamma E_z + \gamma(-v)-B_y \\ &=\gamma(E_z + vB_y) \\ &=\gamma(E + v \times B)_z \\ \\ \end{aligned}\]And the magnetic field:

\[\begin{aligned} (B’)_x &= (F’)^{23} \\ &= L^2_{\;\mu} L^3_{\;\nu} F^{\mu\nu} \\ &=L^2_{\;2} L^3_{\;3} F^{23} \\ &=B_x \\ \\ (B’)_y &= (F’)^{31} \\ &= L^3_{\;\mu}L^1_{\;\nu} F^{\mu\nu} \\ &=L^3_{\;3}L^1_{\;0}F^{30} + L^3_{\;3} L^1_{\;1} F^{31} \\ &=\gamma (-v) (-E_z) + \gamma B_y \\ &=\gamma(B_y + v E_z) \\ &=\gamma(B - v \times E)_y \\ \\ (B’)_z &= (F’)^{12} \\ &= L^1_{\;\mu}L^2_{\;\nu} F^{\mu\nu} \\ &=L^1_{\;0}L^2_{\;2}F^{02} + L^1_{\;1} L^2_{\;2} F^{12} \\ &=\gamma (-v) E_y + \gamma B_z \\ &=\gamma(B_z - v E_y) \\ &=\gamma(B - v \times E)_z \end{aligned}\]These calculations can be checked against here.

In our specific example, we are interested in $(E’)_y$ for the case where only $B_z$ is nonzero. We can see that the above simplifies to:

\[(E’)_y = -\gamma v B_z\]Which says that a purely magnetic field will transform into an electric field under the Lorentz transformation as desired.